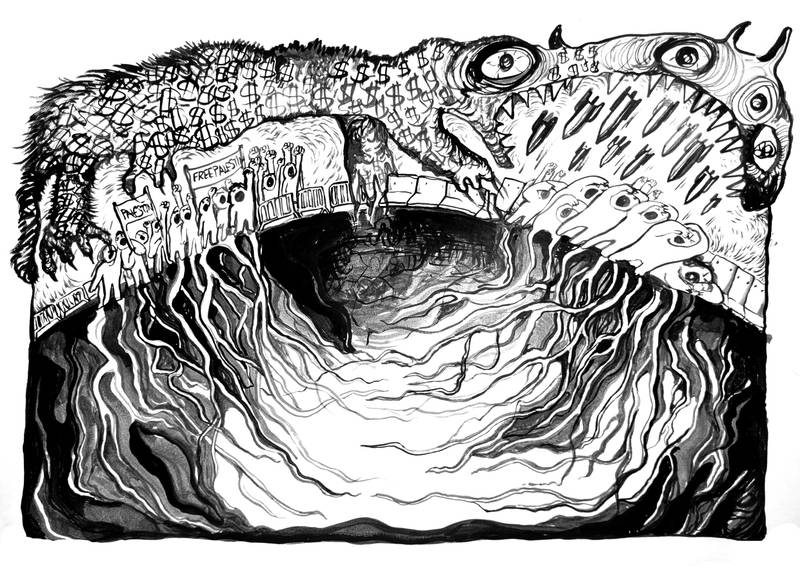

Illustration by Golrokh Nafisi

Elham Rahmati (b. 1989, Tehran) is a visual artist and curator based in Helsinki. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN. In 2019 and 2020, she worked as the curator and producer of the Academy of Moving People & Images (AMPI), a film school in Helsinki for mobile people.

Vidha Saumya (b. 1984, Patna) is a Helsinki-based artist-poet. She is the co-founder and co-editor of NO NIIN – an online monthly magazine in Finland, and a founding member of the Museum of Impossible Forms – an award-winning cultural para-institution in Kontula, Finland.

Elham Rahmati

Our identities are ever-changing due to the accumulation of experiences, thoughts, and interactions with the world around us. Some years ago, my mother showed me a diary she had written when she was 19. She had started writing it at the beginning of the new year, and the revolution had succeeded at the end of the year. By that time, based on the evidence of her diary’s content, she was a different person; she was a revolutionary. She stopped caring about the small details of everyday life, petty interactions with friends and family, or what she had to eat for dinner. Instead, she expressed opinions and concerns about the rights of workers, women, and students; she wanted to know what it means to be truly free. All of her major life decisions following that year have traces of that experience, her work, her marriage, and how she raised my brother and me.

I wrote my last editorial at the end of 2022 while Iran was witnessing a major uprising for ‘liberation’ under a slogan called Jin Jiyan Azadi (Woman, life, freedom), which had originated within women-led Kurdish movements. Today, writing this editorial for our third print volume, is the 176th day after the escalation of the horrifying genocide of Palestinians in Gaza by the settler-colonial, apartheid state of israel. Since then, we’ve seen the pro-Palestine movement ever louder, stronger and more determined than before, taking over public and private spheres—well, at least some of them.

Finland has been a peculiar spot to join the movement from. Despite the tireless efforts of different organisations and activists, the number of people taking to the streets hasn’t exceeded a few thousand, and that is despite the protests being the mildest and least disruptive one can experience anywhere (safer spaces guidelines are even read before the start of demonstrations for some strange reason). The Finnish state has shown complete disregard and moved on to finalising a €317 million deal with israel, sending humanitarian donations to them, and even temporarily freezing support from UNRWA. The art institutions that we’ve been adamantly hopeful of “changing” either remained silent, issued infuriating both-sidist statements of solidarity or just asked for a ceasefire alone, not an end to the occupation nor an end to apartheid, no call for boycotts, divestments, or sanctions.

Some months ago, I joined a 3-hour sit-in for Palestine at Helsinki’s railway station, taking over the space right before people’s entrance to escalators that would take them to the metro, making sure we were disruptive and visible enough for everyone to take notice. Yet jarringly, I saw many people not taking even a glance, not bothering to remove their headphones, just quickly passing us by and going about their day. It’s unsettling how freely people remove themselves from situations in which they and their states are far from innocent. The violence that is at the core of this indifference is rooted in an unapologetic white supremacist belief that, contrary to its favourite slogan, “All Lives Matter," is convinced that some people are insufficiently deserving of a good life, and since that is the case, they are entitled to those people’s lands, resources and culture.

Outside of Finland, in Iran, I received a barrage of sarcastic remarks from friends and family, questioning why I seemed to care more about the Palestinian struggle than the Iranian one. This lack of empathy is often blamed on the state’s disengious co-optation of solidarity with the Palestinian struggle, which would not be completely untrue if the “persian” majority of the country weren’t deeply racist towards Arabs, Afghanis and generally any living organism to whom we can afford to feel superior to.

While in Tehran, I met G, an artist whose work and thoughts I admire. She was excited to tell me about her experience participating in the pro-Palestine movement in the Netherlands and how impressed she was at the surprising turnout of the Dutch people, who previously had little idea of the Palestinian struggle. To encourage that presence, she had the idea of making propaganda-esque imagery out of the people she had encountered. She also told me about events she’s held in Tehran to open up public and private spaces to discuss the idea of Palestine and how it’s relevant to us, and how that was met with an enthusiastic response from those who attended. I didn’t get as excited about her ideas. Somehow, it seemed awful to me to rejoice at the idea of a few white people and Iranians transforming their narcissistic political identities and learning/unlearning via a genocide. I made sure to remind G that these transformations rarely stick around; after a ceasefire is reached, the same people will go home and gradually forget about everything they learned, that these newly-formed dissident identities are borrowed at best, and that we shouldn’t rely our hard-earned hopes on these people and negotiate with their deep-seated liberal mindset that does little but slow down our movements.

G was not happy with my response. She said that although she understands my pessimism is a survival tool in navigating treacherous gaps between illusions of hope and grim reality, I need to know that ultimately there is not much difference between my contemptuous approach and that of the whiteness I complain about. I too am measuring my supposedly revolutionary capacity based on a loss-and-profit ratio. After all, what remains of our revolutionary politics if it is hollowed out of any sense of generosity and compassion?

I had to sit with that conversation for a bit. Had my pessimism been a temporary solution for dealing with having to live with the shame of watching the daily horrors inflicted by racist, zionist, imperialist, colonialist and capitalist ideologies? And isn’t it true that our movements against them have seen more setbacks than achievements? What does that shame accomplish apart from alienating us from the collective political sphere into a personal one where we merely resign to creating an illusion of self-progress? Failing to interrogate the social and historical conditions that reinforce that comforting scepticism. There is, after all, less complexity in life in a world where the sufferings and crises of colonial modernity are naturalised and depoliticised and it’s there that we allow our pessimism to be the reason we root for the failure of people, their transformation and their efforts for change. In that light, how can we adopt an expression of pessimism that sees suffering and our unavoidable limitations on the one hand while also motivating a hopeful critical position that stands firmly against oppression, anywhere and for anyone?

Finland, as I said, is a peculiar spot to join the movement from. Things move slowly and undramatically, which perhaps gives you the chance to see what happens around you rather clearly. On October 17th, I was invited to a WhatsApp group made by a very newly formed intersectional organisation called Sumud that works to end israeli apartheid, occupation and colonialism and to realise Palestinian human and political rights. The purpose of the group was to encourage active participation in organising demonstrations and events calling for a free Palestine. Since then, 500 people have joined. Everyone has to introduce themselves upon joining. I’ve read many accounts of people with no background in activism, having just learned about the Palestinian cause, wanting desperately to be of some use to the movement, to find others who are as devastated by them, and to not go through this moment alone. Six months later, many are still active, showing up every Saturday at 15 at the Railway Square in minus-degree weather. I think about every single person (white or Iranian included) I know who hasn’t and will not allow their life to go back to normal. I think about students who’ve resisted their universities against censorship, even succeeding in getting them to cease exchange with israeli universities. I think about every immigrant in the police state of Germany risking arrest and deportation but still not giving up.

Where we are now and who we are becoming is laying the groundwork for what is to come, and what is to come is an all-encompassing will to collectively learn from and imagine alternative ways of conceiving active ‘by any means’ resistance that liberates us from every form of oppression that is perceived as ineradicable. We’ll come to see, without a doubt, in our lifetime, a free Palestine, from the river to the sea.

Vidha Saumya

This past year, the learning that reiterated itself personally and through the publishing work was to form the habit of making sense of political situations, not only those in one’s vicinity but also those that seem far away, and to wring out meaning from what is usually perceived as “troubled times.” Despite all intent, a pessimistic mind, including mine, sometimes wonders what publishing can really affect. After all, so many books have been published, and knowledge is more accessible to acquire than before. Still around us, we find forms of repression, even in the seemingly more progressive spaces, where attempts to restrict what people can read, see, speak, publish, or even appear in public slyly follow the directives of the status quo.

In conditions where our political, intellectual, and ethical dedication are subjected to the severest of tests, critical publishing empowers writers and readers to disrupt the attempts of such silencing. It’s a training ground for possibilities. It reveals inequalities and allows us to look back, reflect, and move forward. Critical publishing holds immense power, especially during times of crisis. It capacitates us in such times to gather every learning, communication, and functionality and reorient our critical and moral faculties while simultaneously processing material to envision new registers and spaces. After these efforts, responding effectively is one’s responsibility. None of this is comfortable and easy, nor is it a quick to-do list. It is always a drawn-out, long-format, often destabilising procedure that culls our compressed thoughts and clever ideas, compelling us to see the patterns and consequences of actions otherwise rendered invisible in the generative capitalist economy.

The tendency to hesitate to speak one’s mind in the face of injustice is an obstacle to our socio-political progress. This unkind act of remaining silent because we claim to ‘not know enough’ isn’t just about a personal failing but a deeply ingrained social habit. It is a social force that prioritises self-preservation over social responsibility. This collective standing back, a refusal to witness and testify, fuels the persistence of oppression, making it difficult to diagnose because it does not come in grand gestures of betrayal but everyday compromises to avoid conflict or discomfort. Surrendering to power prioritises staying on the good side of authority, even if it means ignoring injustice, restricting people’s mobility and demoralising individuals’ intellect. Institutions will not cease to perpetuate neo-colonial ideas, arrogantly asserting control through force, information access and limitations of expression. It is time we ditch the institutions’ gauge and create our own frontiers to shape our ethical lives and open us to the interior lives of others.

Suppose we attend to this with sincerity. As we move through culture and society, we pay attention to what we recognise, relate to and find relevant to where we stand physically and politically and where others stand in relation to us. We often write about topics and perspectives we can’t describe linguistically. In that vein of thought, can we align ourselves to commit ourselves to each other’s vital moments of vulnerability, enriching our intrinsic value to the many identities we live, perform, accommodate and anticipate?

Having written 15 editorials until 2022, Elham and I decided to redirect our editorial work further to strengthen our critical voice. This redirection in the editorial focus aimed to create an ambit where it might be possible both to feel and think anew, to process the emotional surge of new information, and to consider how to react and imagine other realities. We dedicated our time to revising the website for better interaction, simplifying our readers’ access to nuanced and in-depth contributions, reiterating our publishing direction and finding diverse voices to challenge the status quo. It was an exciting new pace and format of work: it is not often that one gets a chance to reflect on previous work and rehone it. A rhythm of reading, responding, and editing created a new momentum that propelled us forward. We edited and published six new issues with meaningful texts and artworks that frame the unique year that 2023 was. Each contribution in this volume adds to the readers’ collective knowledge(s) of the world and builds a collective capacity to connect changes, resistances, and work in cultural locations distinct from one’s own.

Beyond thinking of publishing as a timely responsibility towards our environs, I propose it as an ‘organising strategy’ to comprehend what it means to care, to recognise what forms a uniting interest, to be invested in criticism, and to understand how the multi-part process of writing, editing, formatting and making public concerns its intent of resistance and repair. Only then does it become possible to approach knowledge and uncertainty amid rapid political and cultural change. Only then can we rely on knowing what’s to come and be engaged in steady preparation. By this, I don’t mean a hasty, haphazardous expelling of all energy at once but instead, a slower, ongoing approach that gathers information, traces links and makes that which has been hidden visible to speak truths that were otherwise silenced. While one may anticipate disappointment and anger, as Maya Angelou says, we must not turn bitter. Creativity and an ‘imaginative present’ have the capacity to nourish us.

Creative imagination is mainly fuelled by criticality. How must we uphold criticality in a continuously depoliticised environment where “energies “ and capacities are subdued to a bland neutral? If we are not vigilant and regularly question our actions and words, politicised words meant to mobilise us can easily be subjected to being inconvenient and complicated and eventually lose their potential to empower us. Critiquing systems of power is not a one-time effort but an ongoing endeavour to find meaningful directions, often at the risk of threatening one’s comfortable conditions of living and working. Ideological investments, legacies and inspirations must be regularly subjected to witnessing their claims of democracy and human rights. Through this process, we habituate ourselves to rejecting the approval of a repressive system, and we gain the ability to collectivise, organise and agitate together in moments of historical urgency.

Similar to geopolitical environments, the status quo within art and culture prioritises and fantasises about singular representation to absolve themselves of the aporia they feel with a sense of ‘urgency’. Perhaps this repetitious and overused ‘urgency’ is so internalised that formulaic, short, clever, and easy-to-follow answers stand ready, but the in-between, the before, the before after, and the nuanced is omitted, even when we tell our stories, that is, if the space to do so even exists anymore. I’d like to think that publishing is neither to remedy the past nor to keep diagnosing the present. It is to desire an extensive involvement in bringing together our different capacities: no breadcrumbing or band-aiding but a collective recognition and understanding of our various languages and punctuations.

Engaging in critical publishing has freed us from treading forward with overt caution or being anxious about upsetting ‘important’ people. It comes with its conditions and difficulties because we are not free from our sentiments and capacities. Still, to enjoy this position, it becomes empirical to be unusually responsive to the messy and invisible, those in transit and complex histories, those who are not habituated to the ways of the status quo, and to endorse that risky mind whose technical competence is undomesticated by the “ways of the world," the audacious, daring, and unstill mind.

Every publishing platform and agency has an audience, field, or scene that must be kept engaged. Now, as editors, whether we keep our audience complacent and happy or stir their minds and mobilise them into more democratic participatory engagement is the challenge. But it would be denaturalising the magazine’s intent if we were to internalise the fear of the powerful. No matter how difficult it gets, one can be consistent with one’s beliefs while remaining free enough to grow, change one’s mind, and rediscover.